Istanbul Modern and Its Discontents

Complicity with autocracy can tar the sleekest of reputations, as we have recently witnessed in Istanbul’s art scene

Last month, ArtReview published my investigation into the growing political pressures on Istanbul’s art scene in the wake of the latest presidential and parliamentary elections. Since Turkey’s autocrat, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, triumphed in the first and second rounds of May 2023’s elections, my artist and curator friends fear hard times await the art scene. After all, a coalition of far-right politicians, who hold the country’s reins, have spent months demonizing leftist and LGBTQI people to win elections.

Yet it wasn’t the fears of my friends and the extremities of Turkey’s government that ended up inspiring my essay. It was an image I encountered on television.

On May 19, I watched Erdoğan deliver a speech on all the wonderful things his party has done for Turkey’s art world during the opening of Istanbul Modern’s new building. Turkey’s president reminded the ‘brutality’ of ‘vandals‘ who dared organize protests against his rule a decade ago, at Istanbul’s Gezi Park.

As the camera cut to the audience, I saw the strongman’s Director of Communications chatting happily with the museum’s Founder. It was an embarrassing yet eye opening moment.

In cahoots: Erdoğan’s director of communications and Istanbul Modern’s founders

I sent a screen grab of the moment to a journalist friend in the US to express my frustration.

Then I wondered whether there was anything to be surprised about the warm friendship of Turkey’s autocrat president and its bourgeoise.

Interviewing critics, organizers, artists and curators, I could see how torn those people were. On the one hand, they admire the culture industry established in Turkey over the past three decades. They want to preserve it, but also consider it complicit in all that is wrong with Erdoğan’s New Turkey.

Then there is this argument I’ve been hearing with increasing frequency: “Being too critical… is exactly what Erdoğan wants—infighting between various representatives of his opposition is good for the government, so stop it.” Yes, the so-called ‘White Turk’ bourgeoisie is not great, but aren’t the Islamists even worse? What if all the things we approach critically today—Istanbul Modern, the Turkey pavilion at the Venice Biennial, etc—are taken away from us and the Islamists impose totalitarian control over the culture industry? Would that be better?

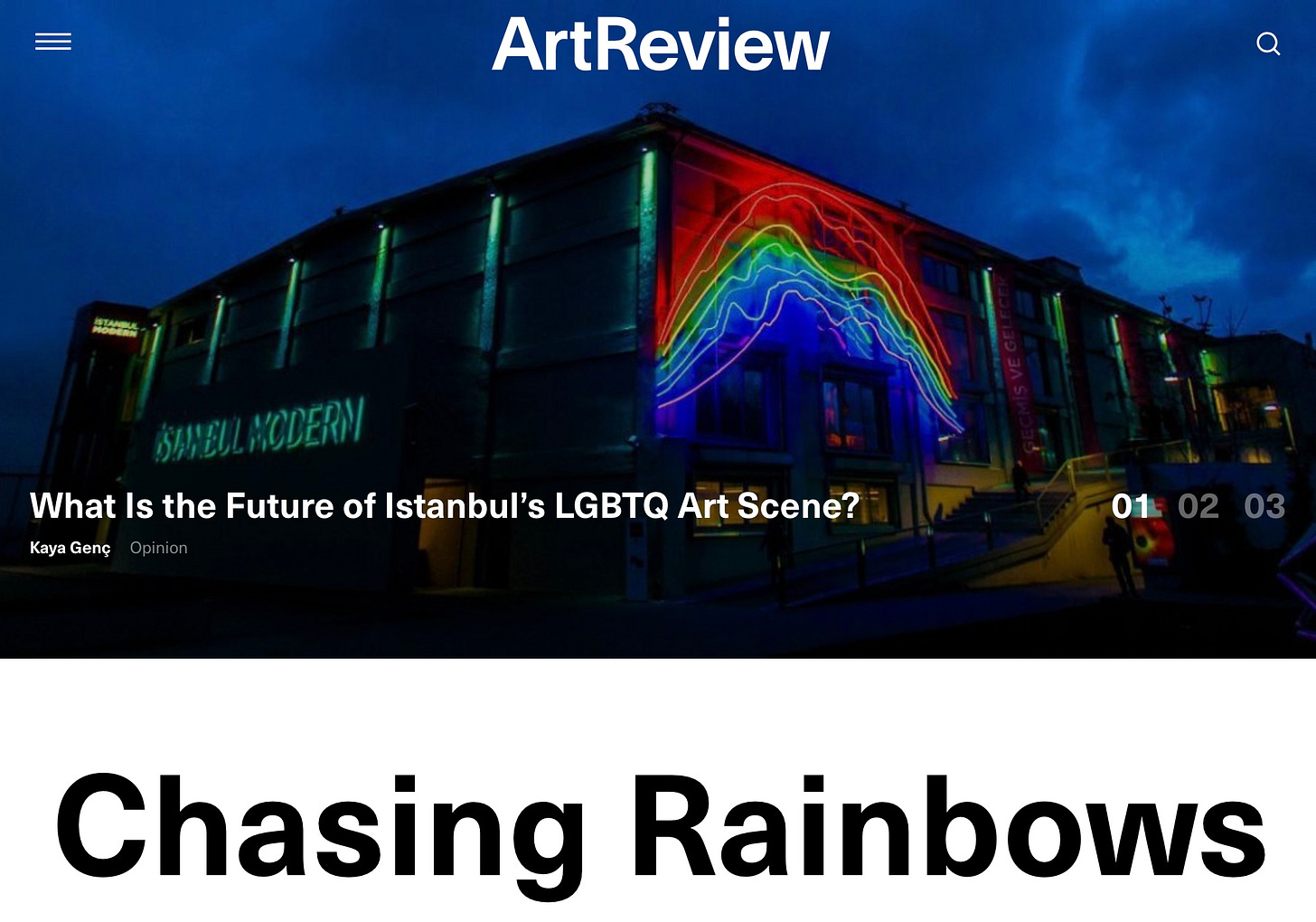

Life is good when you put this rainbow neon work by Sarkis on ArtReview’s front page

Yet such thinking makes it hard to produce critical thinking among scholars, critics, journalists, curators, and artists living in Turkey. Until institutional critique moves to the centre of our art scene—to the heart of its conversations, organizations, exhibitions, publications— this climate of self-censorship and complicity will sadly continue.

Last month, I had another exciting opportunity—to write about John Craxton for Artforum. The occasion was a show at Istanbul’s Mesher. Here was an another artist whose work was on display in Istanbul in all its glory, while his queer identity was carefully hidden from viewers.

John Craxton, another artist whose work is on display in Istanbul, while his queer identity is carefully hidden from viewers

This, I’m afraid, is turning into a pattern. While Turkey’s supposedly progressive institutions murmur and conceal their politics and identities, the propaganda apparatus of the autocratic state is increasingly vocal about the government’s hatred of leftist thought and queer identities.

We should learn to be bolder, I think. We should prepare to burn bridges with our institutions and bosses when necessary. The alternative is to be associated with things one should avoid being associated with.

WhatsApp messages are useful when you want to remind yourself what you said when

Until next time,

—Kaya